Readers of the blog may find this post an unashamedly populist diversion, but bear with me! At the weekend, I had the opportunity to visit Banksy’s “Dismaland” attraction in Weston-Super-Mare. This famous, and hugely successful, event, saw Banksy transform a disused and derelict lido into a anarchic and eclectic art exhibition, featuring pieces from 61 artists (including Banksy himself and Damien Hirst). Among the pieces exhibited was Jimmy Cauty’s “The Aftermath Dislocation Principle”, a 448 square feet model of the aftermath of an unexplained riot. The location of this “miniaturized post-apocalyptic world”? Bedfordshire.

Bedford, as we have discussed before on this blog, was invested with a special significance by members of the Panacea Society. A middle-class haven in the early twentieth century, Bedford’s modern genteel leanings belie a rich tradition of non-conformist protestantism. Most notably, the region was home to John Bunyan, whose Pilgrim’s Progress powerfully shaped Christian religious culture in Britain, charting “Christian’s” allegorical journey to the “Celestial City”. (Those who find themselves in Bedford may be interested in the Bunyan Museum, just across the road from the Panacea Society Museum).

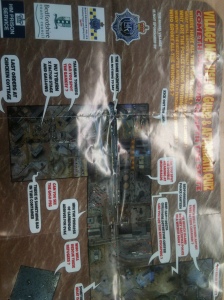

The Panaceans imagined their corner of Bedfordshire to be the original site of the Garden of Eden, and the site where the returning Christ would eventually make his home. Cauty’s vision is markedly different: his post-apocalyptic Bedfordshire sees the county populated only by luminous-jacketed police staring in wonder and horror at the scenes of destruction that have been inflicted on the landscape. A McDonald’s “drive-through” with a tanker protruding from its walls; jagged edges of the model overlooking an abyss; a burning church standing alone on a hill.

Bringing Cauty’s and the Panaceans’ apocalyptic Bedfords into conversation with one another is intentionally anachronistic. I do so to draw attention to distinctive features at the heart of eschatological thinking within much of Western religious thought (i.e. debates about “the end” or “the last things”). Visions of the end mix destruction with idealised recreation, and they are frequently geographically located, even as they claim to be universal and global in scope. Eschatological speculation in the Bible, with its evocative visions of divine wrath and destruction, often focus on specific places. Revelation 17-8, for example, famously singles out “Babylon” (aka Rome) as a target for destruction. It also zooms in on Jerusalem, depicting it as “Sodom and Egypt, where also our Lord was crucified” and envisioning an earthquake destroying a “tenth” of the city and killing seven thousand people (11:8, 11). Cauty’s Bedford zooms in on the destroyed “post-apocalyptic” world, lingering on images of desolation, upturned highways and destroyed buildings. The leaflet accompanying the installation playfully asks “Where have all the people gone?” as the wreckage of the industrialised landscape smoulders, leaving only the model police behind.

Cauty has, to my knowledge, not given thought to his chosen location of Bedford. This feature on the installation suggests that a number of home-counties locations might have been under consideration: “it just feels right and could have easily been Surrey”, the setting for H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. The site of Cauty’s “apocalyptic” riots is ostensibly chosen for its incongruity: a (relatively) central and middle-class county which could be overrun and destroyed by a popular riot, before swiftly being brought back under police control. We might even question whether Cauty’s “post-apocalyptic” Bedford is in any sense a religious eschatological vision, rather than being purely a political commentary on the modern state and the role of the police, law-enforcement and commercialism within it.

Key aspects of Cauty’s installation, as well as his own career might caution us against erasing religion entirely from view, however. The burnt-out church on a small hill in the corner of the exhibit features prominently in the installation. Similarly, in the installation’s leaflet, a burnt-out patch of grass is annotated with the question “On which island do they sacrifice police in a wicker man?”

The reference to the “wicker man” is a clear reference to the seminal 1973 film of the same name, where a devoutly Christian police officer is burnt alive as part of a pagan ritual. It may also, however, allude to Cauty’s own past work as part of the band the KLF. Sacrifice and ritual constituted consistent themes across the KLF’s works, and in 1991, Cauty and bandmate Drummond invited 80 music journalists to the Scottish Island of Jura, dressed them in saffron robes and celebrate the Summer solstice by burning a wicker man. The event is featured prominently in the KLF’s short film “The Rites of Mu” (available on youtube). Given Cauty’s evident interest in ritual, sacrifice and religious mythology, perhaps his designation of his alternative Bedfordshire as “post-apocalyptic” can’t be completely expunged of its religious connotations?

The Panacea Society’s Bedford is, in many respects, a counterpoint to Cauty’s riot-ravaged wasteland. It was envisaged by the society’s founders as a place of spiritual and religious renewal. Mabel “Octavia” Barltrop, the society’s leader, sang Bedford’s praises in a letter to fellow Panacean Ellen Oliver on March 26, 1919. Through a complex series of interpretative leaps, involving much speculation about the Hebrew origin of the word “Bedford”, Barltrop linked the town with Goshen – the land given to Joseph by Pharaoh in Genesis 45:9-10 – and eventually to Jerusalem.

I have such a feeling that somehow Bedford is a sort of “Goshen” that perhaps it is Beth-ford as d & th often interchange. Beth = house. ah! Beth-ell-ford a little bridge to the house of God – Jerusalem! Bunyan you know was prisoner here also John Howard the prison reformer lived here.

Mabel Barltrop, letter to Ellen Oliver, March 26, 1910 (PS 4.2/3)

Barltrop’s designation of Bedford as a “bridge” to (the new?) Jerusalem, indicates how prominently the town featured in her own thought about the promises of the end offered to her fellow believers. She imagined her town and community to be the centre of the expected transformation of the world from a place of sin and divine alienation, to the idealised, utopian world prefigured in the Bible. That Bedford was also home to such influential people as Bunyan and the prison reformer John Howard could only bolster its special significance in Barltrop’s eyes. For Barltrop, as for Cauty, Bedford was the site of an apocalyptic transformation. Only for Barltrop, her expectation was that the town should not be a site of divine destruction, but rather would act as “the new Jerusalem” in which peace would reign and Christ would dwell with humanity.

Whilst I doubt that either could have conceived of the other, Cauty and the Panaceans present us with a tale of two cities: of two Bedfords transformed beyond recognition by an apocalyptic event. Just as the prophetic books of the Bible imagine Jerusalem both as a site of destruction, and of utopian restoration, so too Bedford is seen through these two visions as a landscape in which the dialectic promises of “the end” can be worked out. Cauty’s “post-apocalyptic” riotscape, and Mabel Barltrop’s English “Goshen”: both Bedfords present competing, yet intertwined, facets of Christianity’s eschatological hope – the destruction and recreation of familiar urban landscapes and structures.

Further suggested reading:

- http://jamescauty.com/work/the-aftermath-dislocation-principle/

- John Higgs, The KLF: Chaos, Magic and the Band who Burned a Million Pounds (London: Phoenix, 2013)

- Jane Shaw, Octavia, Daughter of God: The Story of a Female Messiah and her Followers (London: Jonathan Cape, 2011)